The Right to Bubble-Wrap Your Kid?: Mahmoud v. Taylor FAQs

On June 27, 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Mahmoud v. Taylor: A case that will profoundly change the nature of public education in the same vein as Brown v. Board of Education or Tinker v. Des Moines.

In a rare accomplishment, this ruling pisses off school districts and civil rights advocates, two groups that are usually on opposite sides. The case also sets the record for “Most Children’s Books Cited in a Supreme Court Case” since the court’s conception in 1789 (the judges don’t talk about books with puppies a lot…).

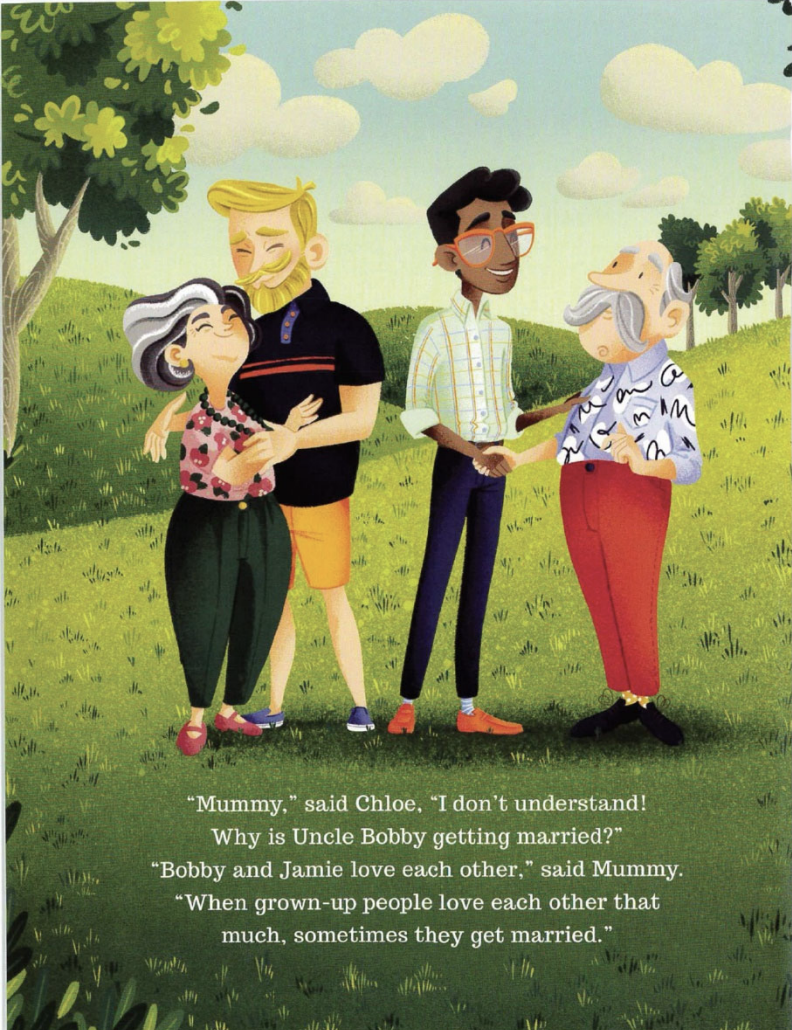

We previously mused about Mahmoud v. Taylor here. A group of religious parents sued a Maryland school district when the district did not allow them to opt-out their young children from instruction that included books with universal themes using LGBTQIA+ characters (For example, a child feeling anxious about her beloved uncle getting married and how that may affect their relationship. The uncle happened to be marrying a man). The lower courts held: “Mere exposure to views contrary to one's own religious beliefs [does not] necessarily constitute a cognizable burden" on the free exercise of religion. But SCOTUS disagreed.

At its heart, Mahmoud v. Taylor asks: Can parents bubble-wrap their children in public school from any material that offends their religion?

In a 6-3 decision, the Court said yes. But only if three factors are met:

young students (younger children are subject to pressure from authority figures more so than older children)

moral framing (presenting a child’s dissent to inclusive topics as bigotry or just plain wrong)

lack of notice or opt-out (if the state does not provide any sort of procedural accommodation)

Q: What is “opting out”?

A: For decades, there has been a movement for parents to “opt out” of certain portions of public school instruction. Parents have attempted to opt out their children of human sexuality education (successfully: states ubiquitously have “opt out of sex ed” laws), standardized tests (not as successfully, except for a few states), and everything in between.

Mahmoud v. Taylor holds that a school must give parents notice of material that may offend their religion, with a process for opting out their children from that material and providing them an alternative learning opportunity, when the children are young, attendance is mandatory, and the material is presented as “right” or “normative.”

Q: Is this a book ban?

A: No, Mahmoud v. Taylor does not endorse book bans. Some culture war activists go too far in calling this ruling a book ban. This case is a clumsy attempt by SCOTUS to balance the needs of a pluralistic population accessing public education.

Logistically, a book ban case would be far easier: schools simply would be prohibited from shelving certain identified books in their classroom libraries. Of course, a book ban would also be far harsher and likely illegal, erasing LGBTQIA+ children and families from public life.

Instead, Mahmoud v. Taylor suggests that schools should provide notice to parents of books and material that could potentially infringe their religions and allow the parents to request alternative instruction. The Court did not say that exposing children to ideas contrary to their faith is unconstitutional; the key, according to Justice Alito’s opinion, was the combination of “normative messaging and institutional reinforcement” with elementary-aged children.

The majority pointed not only to the content of the books, which portrayed same-sex marriage and gender transition as joyful and self-affirming, but also to the teacher guidance documents in which the school instructed teachers on how to respond to children’s comments such as “A boy can’t marry a boy!” Teachers were told to respond, “Two men who love each other can decide they want to get married.” (note: a true statement since 2016.)

In reality, many schools will over-comply with this ruling and proactively remove inclusive material from their shelves, harming under-represented children and families. Mahmoud v. Taylor does not require or endorse the removal of queer-inclusive books (or books that depict characters joyfully eating pork or women skipping merrily in shorts).

Q: What does this case have to do with the Amish?

A: The court relied heavily on a 1972 landmark case, Wisconsin v. Yoder, to determine that a Christian child’s exposure to queer-inclusive texts in public school was similar to prosecuting Amish parents for failing to send their children to high school.

When Amish parents were criminally prosecuted for not sending their children to school past 8th grade, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the state was infringing on their rights to practice their religion.

In Yoder, SCOTUS decided that a Wisconsin state law compelling attendance in public school until age 16 was an unconstitutional infringement on Amish parents’ sincerely held religious beliefs, which opposed formal education beyond the eighth grade. SCOTUS agreed with the Amish parents that the state was infringing on their rights to practice their religion.

Many parental-rights groups have attempted to use Yoder in the last decade to oppose trans-inclusive policies in public schools, such as bathroom policies that allow students to use bathrooms of their gender identity. Their argument has consistently failed in the past, with almost all courts holding that Yoder involved a very different fact pattern with compelled attendance (not exposure to issues at school).

In Mahmoud v. Taylor, SCOTUS reversed course, holding that Wisconsin’s compelling Amish parents to send their children to high school in Yoder was similar to the Maryland school’s infringement of religious parents’ rights to protect their children from LGBTQIA+ inclusive texts.

Justice Alito’s opinion engages in some mental gymnastics by quoting the Court’s own opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, which allowed for same-sex marriage nationwide. Alito writes: “many Americans advocate with utmost, sincere conviction that, by divine precepts, same-sex marriage should not be condoned,” and because the storybooks present “same-sex weddings as occasions for great celebration” where a marriage is “acceptable” if two people love each other, these books “present the opposite viewpoint to young, impressionable children who are likely to accept without question any moral messages conveyed by their teacher’s instruction.” One wonders if the storybook presented same-sex marriage as a somber fact of jurisprudence, instead of a “joyful celebration” or “acceptable,” the Court would reach the same conclusion.

Q: What do school administrators need to do now?

A: Right now, nothing. But get ready by reviewing curriculum instruction for elementary-aged children.

The ruling only applies to the parties in the case (the plaintiffs and the defendant Maryland school district), so there’s no affirmative obligation on other schools to proactively do anything. Absent a state law requirement, there’s no need to start printing off opt-out forms for parents to submit for alternative instruction based on sincerely held religious beliefs.

SCOTUS made clear that the problem in Mahmoud v. Taylor was not passive exposure to diversity or inclusion of diverse texts in the instruction: it was the “curriculum designed to present certain values and beliefs as things to be celebrated, and certain contrary values and beliefs as things to be rejected,” combined with the young age of the children, mandatory attendance, and lack of opt-outs.

In other words, it wasn’t unconstitutional that Pride Puppy or Uncle Bobby’s Wedding was included in the curriculum. It was the district instructing teachers to respond to a five-year-old child who says “You can’t say you’re a boy if you were born a girl!” with “That comment is hurtful.”

We will likely see state legislatures move for broader “opt out” laws. “Opt out” laws broadly exist for sex ed, but some states go further and allow parents to review the instructional materials provided to the child and if the parent objects to the content, the school must “make reasonable arrangements . . . for alternative instruction” (SCOTUS cited Minnesota’s broad opt out statute as an example law.)

Schools are familiar with the idea of “notice and opt out” provisions thanks to sex ed, FERPA, and other state-specific provisions that require an annual opt out to be published (usually in the student handbook at the start of the year).

Q: If a parent opts their child out, what alternative activity do schools have to provide?

A: Each school decides.

In some state laws, the parent can make their own “alternative instruction” if “the alternative instruction, if any, offered by the school board does not meet the concerns of the parent.”

This is obviously an enormous administrative burden to schools. In Mahmoud v. Taylor, the school district argued that universal opt-outs sought by religious parents were “infeasible” and “unworkable;” the only reason opt-outs for sex ed are effective is because sex ed is a “discrete” and “predictably timed” exception.

SCOTUS rejected that argument, stating if schools can have a “robust system of exceptions” for special education pull-out instruction and for sex ed instruction, then universal opt-outs should be easy too! (Note: No SCOTUS justice has ever taught in K-12 public schools.)

Students who are entitled to special education, but also need opting out of instruction, would need their special education services provided in the same least restrictive setting.

Q: Should schools remove books with any queer characters, to get ready for the backlash and administrative headaches?

A: No. Do NOT remove books with LGBTQIA+ inclusive themes, and don’t start trying to guess what books will offend. While the books in question had LGBTQIA+ characters, such as two men marrying in Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, there is a myriad of topics that may be offensive to the major religions practiced in the United States. Consider if your school material contains any of these topics or characters which could offend interpretations of the major religions…

women with uncovered hair or short hair

divorced couples

men or women wearing shorts above the knee

evolution or dinosaurs

women wearing pants or shorts

eating pork, shellfish, beef, or dairy and meat together

drinking caffeine

men wearing silk or gold

wearing wool and linen together

wearing jewelry

women working outside the home or holding positions of leadership

dancing

interest rates

mixed-gender socializing

going to therapy or seeking mental health supports

We could go on, but you get it.

Every public school in America contains material that some interpretation of some religion would find objectionable. (As pointed out by Justice Brown Jackson, the child of two public school teachers, in her dissent.) Trying to guess all of those themes and removing them is an administrative burden to educators and a dangerous burden on historically underrepresented children.

If schools had to provide notice to parents of all materials that may offend any interpretation of any religion, materials depicting women in pants, women in leadership positions, and women working outside the home may become problematic.

The lesson from Mahmoud v. Taylor is that these books or lessons, when presented to elementary-aged children by authority figures, should not include a lesson of “right vs. wrong” on religiously controversial issues without parents being able to opt out. If schools want to instruct children that their objections or questions about, for example, transgenderism are “hurtful” or wrong, parents need to know and be able to opt out.

Imprint Legal Group advises schools and businesses on legal compliance and inclusive cultures. To discuss any questions about your particular situation, training opportunities, or media inquiries, please contact: hello@imprintlegalgroup.com.

All posts of Imprint Legal Group and its authors are intended as information, not legal advice. This information is valid as of July 14, 2025.